“Decompression ceiling, cave or wreck, it’s all the same. If it comes to a problem you can’t just go up”. How many times I had heard or read these words I’m not sure, but thinking back and scratching my head it actually amazes me to think that that I once accepted this as being true.

Re-evaluating that statement was one of the things that started to happen the moment my formal wreck training began. All of that open water deep diving experience, the notion that I’d got everything pretty well worked out and that there couldn’t be that much more to it than I was already accomplishing, that belief began to fall apart as soon as the course began taking shape. It opened the door on a vast new field of skills and techniques that one has no option but to get to grips with and attempt to master, and forced a complete reappraisal of the ‘decompression and overhead are all the same ‘ philosophy. Because they aren't.

My training was conducted many years ago, with long time dive buddies as classmates, in the hands of the already vastly experienced Alex Santos. It began with a dry dive. A line drill simulating a penetration around a kids playground. Straightforward so far, a few minutes of work and we were advised that we’d reached thirds on our imaginary air supply and should head out. Simultaneously Alex blindfolded us, simulating the unthinkable – complete light failure. We groped sightless along our guideline until casually informed “ Sorry lads, you’re dead now.” This was rude awakening number one. If it had taken five minutes to go in on a third of the available air, then ten minutes worth was available to exit. Blinded and dramatically slowed, out time ran out and we had drowned. The simple lesson, don’t ever, ever rush a penetration or you will be faced with having to rush out if in trouble , and now we knew where that would go.

My training was conducted many years ago, with long time dive buddies as classmates, in the hands of the already vastly experienced Alex Santos. It began with a dry dive. A line drill simulating a penetration around a kids playground. Straightforward so far, a few minutes of work and we were advised that we’d reached thirds on our imaginary air supply and should head out. Simultaneously Alex blindfolded us, simulating the unthinkable – complete light failure. We groped sightless along our guideline until casually informed “ Sorry lads, you’re dead now.” This was rude awakening number one. If it had taken five minutes to go in on a third of the available air, then ten minutes worth was available to exit. Blinded and dramatically slowed, out time ran out and we had drowned. The simple lesson, don’t ever, ever rush a penetration or you will be faced with having to rush out if in trouble , and now we knew where that would go.

Beyond such starkly illustrated points, the four days and more than eleven hours spent inside wrecks served to highlight just how much better a supposedly capable technical diver has to become to be genuinely slick on a penetration dive. What did I begin to reflect on? Perfect buoyancy doesn’t give you much without perfect trim and perfect propulsion skills as partners. Communications and awareness? An instinctive ability to assess another divers mental state and stress level by their body language comes easily with years of instructing. But real, effective, light signals, a range of clear and non-ambiguous hand signals, the decision to go to touch contact in a silt out, all were new and required a good degree of conscious effort.

How about new motor skills and co-operation within a team? Cruising a wall, eyeing the fish, watching each other shoot an SMB and do a gas switch – easy. Now add clean, fuss free stage drops and retrievals, S-drills with all three lights, choice of primary and secondary tie offs and correctly placing oneself to illuminate for a buddy making a line wrap or retrieving a reel. Then there is constant surveillance for line traps, taking up slack line for the reel handler, checking valves for roll offs every time you have been near something, awareness of line position when diving away from it, never allowing another diver to be behind you when reeling out of the wreck, and simply knowing what is happening to everyone in your team at all times These are all small things when taken in isolation, but for the big picture, they need to come together without thought. Seeing an experienced instructor monitor us so effortlessly was an eye opening experience.

And next we had equipment. Funny how so much of mine went in the bin right after the course. All those things that were never a problem in open water where they have no capability to distract or give trouble. Those plastic fins, that catch line with their buckles, and the video of myself that persuaded me it wasn’t just my technique that was causing the silt. The SPG hose that was four inches too long and hung up the gauge at every opportunity. Ditto the inflator hose. Lights that burn less than a couple of hours? No help. Reels with handles and lock screws, or a simple unjammable spool? That was no contest. Plastic manifold knobs – now I know they can break! In short it will become apparent that anything that is not helping you in the water will make itself painfully obvious, and usually at just the wrong moment.

And next we had equipment. Funny how so much of mine went in the bin right after the course. All those things that were never a problem in open water where they have no capability to distract or give trouble. Those plastic fins, that catch line with their buckles, and the video of myself that persuaded me it wasn’t just my technique that was causing the silt. The SPG hose that was four inches too long and hung up the gauge at every opportunity. Ditto the inflator hose. Lights that burn less than a couple of hours? No help. Reels with handles and lock screws, or a simple unjammable spool? That was no contest. Plastic manifold knobs – now I know they can break! In short it will become apparent that anything that is not helping you in the water will make itself painfully obvious, and usually at just the wrong moment.

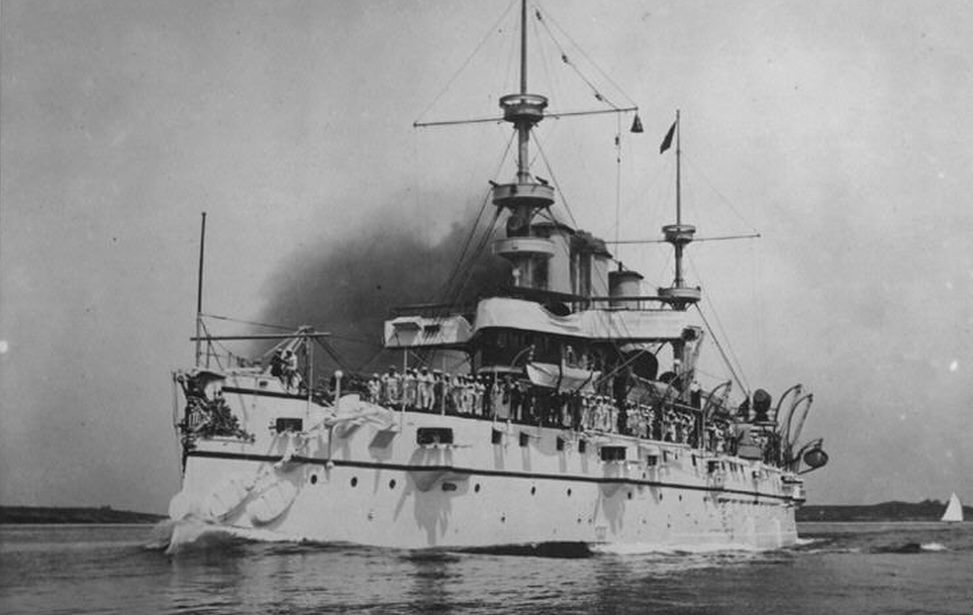

Last of all I came back to that analysis of the situation in which I was now placing myself, four decks deep inside a battle cruiser versus decompressing in open water. The reality myself and others have found is, if someone is having a physiological emergency, a buoyancy blow up, gets tangled in their SMB, or has nothing left to breathe, then decompression or otherwise, you can go to the surface and fix it if you realy have to. Getting back down quick enough will then fix you too. But getting silted out and stuck under tons of steel, that choice and ability to buy time is absolutely not available. I felt how environmentally committed I was in ways I had never felt in open water. This realization clearly hammered home to me the need to do things properly. Good technique, good planning, a team you trust and the right gear.

That accepted, the thrill and reward of becoming a capable wreck diver are beyond measure. I’ve had the good fortune to since lay eyes on sights that I know nobody has ever seen before. All told I would recommend this to anyone with a desire to see themselves grow as a diver. It doesn’t have to be deep, it doesn’t have to start difficult, but it can be an enthralling activity and you will probably never look back.